|

Background

ABOUT THE ART

Benn Pitman (1822-1910), Adelaide Nourse Pitman (1859-93), Elizabeth Nourse (1859-1938)

Bedstead, c. 1882-83

Mahogany and painted panels

Gift of Mary Jane Hamilton in memory of her mother, Mary Luella Hamilton, made possible through Rita S. Hudepohl, Guardian, 1994.61

This mahogany bedstead was designed by Benn Pitman on the occasion of his marriage to his second wife, Adelaide Nourse. Adelaide carved the decorative motifs on the bed, which was made for the Pitman home on Columbia Parkway. The interior of the home was decorated with carved floral and geometrical motifs based on native plant life. Everything in the home was carved by hand, from the baseboards to ceiling moldings and all its furniture.

The bedstead is Modern Gothic in style and is composed of a headboard, footboard, and two side rails. The headboard is divided into three sections: two lancet panels with egg molding and a central trilobate arch. The central panel is carved with a flock of swallows flying in the evening sky. The birds are depicted in various stages of relief, some nearly four and a half inches from the headboard. Others are shown in low relief to suggest a sense of depth. Just below and to the right of the birds is a crescent moon in low relief. Hydrangea blossoms in high relief are carved into the lower section of this panel. In the lower left is a carved inscription that reads, "Good night, good rest." Extending above this is an arched hood that is carved with four panels of overlapping daises. The four finials of the headboard are carved in the shape of wild parsnip leaves.

In the two lancet panels on either side are painted images of human heads on gold discs representing night and morning. These panels were painted by Elizabeth Nourse (1859-1938), Adelaide's twin sister, who was an internationally acclaimed painter. To the left is Morning, surrounded by painted white azaleas. To the right is Night, surrounded by balloon vines. The corners of these side panels are carved with stylized leaves and berries.

The rectangular footboard is divided into three sections and is framed along the top and bottom by a border of stylized leaves. The central panel is decorated with carved palmeris in high relief. The two smaller panels on either side are carved with geraniums on the left and lilies on the right. The interior of the footboard is also carved. It is divided into three panels and is bordered by rosettes. The central panel depicts a wild rose climbing behind a trellis, and the two side panels are carved with poppies. The two rails on either side of the bedstead are decorated with a highly stylized border of leaves and berries.

This bed, which occupied the Pitman's bedroom, was meant to symbolize and celebrate sleep. Soon after its completion, it received much acclaim and was exhibited in 1883 by the Pitmans at the Fifteenth Annual Exhibition of the Work of the School of Design of the University of Cincinnati and also at the Cincinnati Industrial Exhibition. In 1909 the bedstead and the rest of the bedroom were described in the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette: "It is such a room in which a sufferer of insomnia would totter drowsily upon entering. The entire combination is made to symbolize "night" and so faithfully is repose portrayed that sleep nearly overcomes one within the door. The bed is a masterstroke of human genius…and the entire combination seems covered with such a consistent nocturnal veil as to make the words "good night" at the bottom quite unnecessary."

Today, the Pitman Bedstead is considered one of the finest examples of both Cincinnati Art-Carved Furniture and American Aesthetic Movement furniture ever produced. The proponents of the Aesthetic Movement often turned to nature for inspiration in the design and decoration of household items, such as furniture, ceramics, stained glass, metalwork, and textiles. Pitman, a staunch advocate of the Aesthetic Movement in America, designed this bedstead with plants and birds that are all found in the Cincinnati area. He believed it was important that American decorative arts, such as this bed, reflected the landscape of this country.

THE CINCINNATI ART-CARVED FURNITURE MOVEMENT

By the mid-1850s, the leaders on the Cincinnati Art-Carved Furniture Movement had left their native country of England and moved to Cincinnati. These men were Benn Pitman (1822-1910), Henry Lindley Fry (1807-1895), and his son William Henry Fry (1830-1929).

Henry and William Fry, trained as wood-carvers, advertised themselves as designers and carvers of furniture and interiors. As Cincinnati was a major center for furniture manufacturing, almost immediately the community showed interest in their work. Wealthy patron Joseph Longworth, impressed with the carvings completed in his own home, also commissioned the Frys to carve the interior of his daughter Maria's home. Visitors to the home showed great interest in learning how to carve, and by the early 1870s the Frys were providing instruction in carving.

Benn Pitman came to Cincinnati to promote a system of shorthand developed by his brother, Sir Isaac Pitman. Pitman was familiar with carving from his work in printing and aware of the Fry's success, he began making designs for wood carving. In 1873, he established the wood carving department at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, where he taught until 1893.

Lasting over fifty years, the Cincinnati Art-Carved Furniture Movement affected approximately 1,100 people, of those, 912 were women. Displaying their work at large national and international exhibitions, the Cincinnati carvers acquired worldwide attention for their accomplishments. With the turn of the century, carving in the style of the Pitmans and Frys was no longer the fashion, and William Fry taught his last carving class in 1926.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

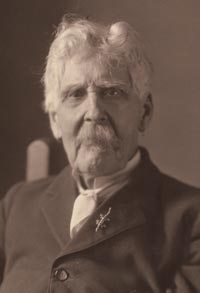

Benn Pitman -- Designer Benn Pitman -- Designer

Birth: July 14, 1822 Trowbridge, Whitshire, England

Death: December 28, 1910 Cincinnati, Ohio

Occupation: Designer, wood-carver, author, teacher, and "phonographer"

Benn Pitman was born in Trowbridge, Whitshire, England, on July 14, 1822. His first training was in architecture, but he decided to assist his older brother, Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897), who invented phonographic shorthand in 1837. This system soon became one of the most used writing systems in the world.

In the early 1830s, Pitman settled in Bath, England, to begin training as an architect. Isaac also had a school there, and Pitman soon became actively involved in advertising his brother's shorthand method. For ten years, he promoted his brother's phonography method throughout England through lectures and teachings. At Isaac's urging, Pitman immigrated to the United States to introduce the country to phonography.

Pitman arrived in Cincinnati in 1853 with his wife and children. Once the family was settled, he established Pitman's Phonography Institute, where courses were offered in the technique. The school became very popular, and Pitman sold hundreds of thousands of copies of his instruction manuals. A student himself of his brother's technique, Pitman served as the official stenographer at the trial of President Abraham Lincoln's assassins in 1865 and at the Ku Klux Klan trials of 1871.

During the 1860s and 1870s, interest in decorative wood carving was growing in Cincinnati, particularly as a result of the work of Henry (1807-1895) and William Fry (1830-1929), two British expatriates who worked as wood-carvers in the city. Pitman also began to experiment in wood carving around this time, although it is not known exactly when he began.

Pitman offered to teach a course in decoration, to provide "instruction in wood carving, metal work, enameling, lettering, and illuminating." His offer was accepted by the University of Cincinnati's School of Design, and in 1873 he headed the newly opened Department of Wood Carving, with the help of his daughter, Agnes Pitman (1850-1946).

During his first term as an instructor, 121 students had enrolled for his classes, the majority of which were women. In November, he reported that "we have in hand, or have completed eight hundred and twenty pieces of work, and have used over three thousand feet of black walnut lumber." In 1876, Pitman's students' work was exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The following year Pitman and his students began work on the decoration of the organ screen, which measured fifty by sixty feet, for Music Hall, which was then under construction. The carving of this massive work was based on forms in nature.

In 1878, Pitman's first wife, Jane, passed away. He remained a widower for four years until he married Adelaide Nourse (1859-1893), who had been one of his students. Over the next twenty years, Pitman, his daughter, and his wife, together with former students, decorated his Columbia Parkway home and all its furniture with carved floral and geometrical motifs based on native plant life. The work was completed in 1905, twenty-one years after the cornerstone was laid.

Pitman continued teaching until 1893. His treatise on decorative art and a compilation of his teachings, titled A Plea for American Decorative Art, was published for the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. He wanted to create an American "look" for decorative arts, based on local plants and wildlife. Many of Pitman's views were based on his philosophical mentors, including John Ruskin (1819-1900), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), and William Morris (1834-1896). Pitman's ideas on the decorative arts positioned him as a staunch proponent in the forefront of the American Aesthetic Movement. Pitman taught his last class in 1893 and died in 1910.

Adelaide Nourse Pitman -- Wood-Carver

Birth: October 26, 1859 Cincinnati, Ohio

Death: September 12, 1893 Cincinnati, Ohio

Occupation: Wood-carver, china decorator, and metalworker

Adelaide Nourse Pitman, the twin sister of Elizabeth Nourse and youngest of ten children, was born on October 26, 1859, in the Cincinnati suburb of Mt. Healthy. Her parents had moved to Cincinnati from Massachusetts in the early 1830s. Her father, a banker, suffered serious financial losses after the Civil War. As a result of this loss, the girls were required to support themselves. The twins enrolled in the University of Cincinnati School of Design, which charged only minimal tuition.

While at the University, Adelaide joined Marie Egger's china painting class and began several years' study of wood carving under Benn Pitman. She worked on the carving of the Cincinnati Music Hall organ screen, carved a number of architectural elements for the interior of the Ursuline chapel in St. Martin, and received a silver medal at the 1880 Cincinnati Industrial Exposition.

On August 10, 1882, Adelaide married Pitman in Sandusky, Ohio. She was twenty-two and he was sixty. After their marriage, she continued to work, under his supervision, in copper, silver, and brass, as well as on decorative wood carvings for the Pitman home on Columbia Parkway.

In 1883 she gave birth to her first child, who died in infancy. The couple's second child, born July 5, 1884, was named Emerson. The third and final child born to the couple was their daughter, Melrose, born on November 5, 1889.

Tragically, Adelaide Pitman died on September 12, 1893 of tuberculosis. She was only thirty-three years old.

Elizabeth Nourse -- Painter

Birth: October 26, 1859, Cincinnati, Ohio

Death: October 8, 1938 Saint Légeren-Yvelines, France

Occupation: Painter, sculptor, wood-carver, etcher, illustrator, and decorative artist

Elizabeth Nourse, the twin sister of Adelaide Nourse Pitman, was born on October 26, 1859, in the Cincinnati suburb of Mt. Healthy. Her parents had moved to Cincinnati from Massachusetts in the early 1830s. Her father, a banker, suffered serious financial losses after the Civil War. Due to this loss, the girls were required to support themselves. The twins enrolled in the University of Cincinnati School of Design, which charged only a small amount in tuition.

While there, Elizabeth received training under Thomas S. Noble, William H. Humphreys, Lewis Cass Lutz, Henry Muhrman, Louis T Rebisso, Benn and Agnes Pitman, Marie Eggers, and others, and graduated in 1881. After she graduated, Elizabeth had planned to continue her studies in New York; however, this was postponed by the death of her mother and the marriage of her twin sister, Adelaide, to Benn Pitman.

In the fall of 1882, Elizabeth spent several months at the National Academy of Design in New York. Upon her return to Cincinnati in 1883 and until 1886, she supported herself as a portrait painter and fresco artist. In 1887 she exhibited four watercolors at the Cincinnati Industrial Exposition. In July of that same year, she and her older sister Louise sailed for France. They spent the rest of their lives abroad, returning only once in 1893 for a visit with their sister Adelaide, who was dying of tuberculosis.

While in Paris, Elizabeth enrolled in the women's class at the Julian Academy. After a few months of study she was advised that if she left the Academy she would improve more rapidly. She did, and within a year of her arrival in Paris, her work hung at the Salon. In December 1893, while she was visiting Cincinnati, the Cincinnati Art Museum organized a solo exhibition of her works. The exhibition was comprised of 102 paintings and sketches in oil, watercolor, pencil, and pastel. Of these works, ten had been shown at the Paris Salons and three had just won medals at the Chicago World's Fair.

In 1895 she became the first American woman to be made an Associée of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, becoming a Sociétaire in 1901. She also had her work purchased by the French government for the permanent collection of the Luxembourg Museum. This was an extraordinary honor for a woman.

Even though her home was in France, Elizabeth made trips to Russia (1889), Italy (1890-1891), Holland (1892), and Tunisia (1897). While in each of these locales she painted the local people. Although Nourse painted landscapes and portraits, her favorite subject matter were peasants, especially women and children. Many of her works were done in oil, as well as in watercolor and pastel, which she used more and more toward the end of her life as her eyesight was failing. Elizabeth Nourse died on October 8, 1938.

An unassuming and shy person, Elizabeth had a delicate way about her. Her good friend Clara McChesney wrote of her in 1896:

"She is quiet and shy in her manner. Her health is very delicate, and it is to the ever faithful care of her sister, who devotes her life to her, that she has been able to accomplish so much and such fine work. It is a strange fact that this delicacy does not show in her work, which has the strength of a man. She was once asked how, being so frail, she could paint out of doors in such cold weather and not feel it, and her reply was that she works with such rapidity and force and with such self-absorption that she is not even conscious of the weather!"

From Artists in Ohio, 1787-1900: A Biographical Dictionary

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aronson, Julie (editor). The Cincinnati Wing: The Story of Art in the Queen City. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2003.

Burke, Mary Alice. Elizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938: A Salon Career. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983.

Cincinnati Art Museum. Cincinnati Wing Teacher Guides: Art Education.

Cincinnati Art Museum. Cincinnati Wing Label Copy: Cincinnati Art-Carved Furniture.

Haverstock, Mary Sayre, Jeannette Mahoney Vance, and Brian L. Meggitt (compilers and editors). Artists in Ohio, 1787-1900: A Biographical Dictionary. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2000.

Howe, Jennifer (editor). Cincinnati Art-Carved Furniture and Interiors. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2003.

|